Royal St. George's Golf Club

Royal St. George’s has evolved over the years but retains the wildness, charm, and compelling difficulty that first captured the imaginations of golfers in the late 1800s

December Virtual Hangout - Courses that Left an Impact On Us in 2025

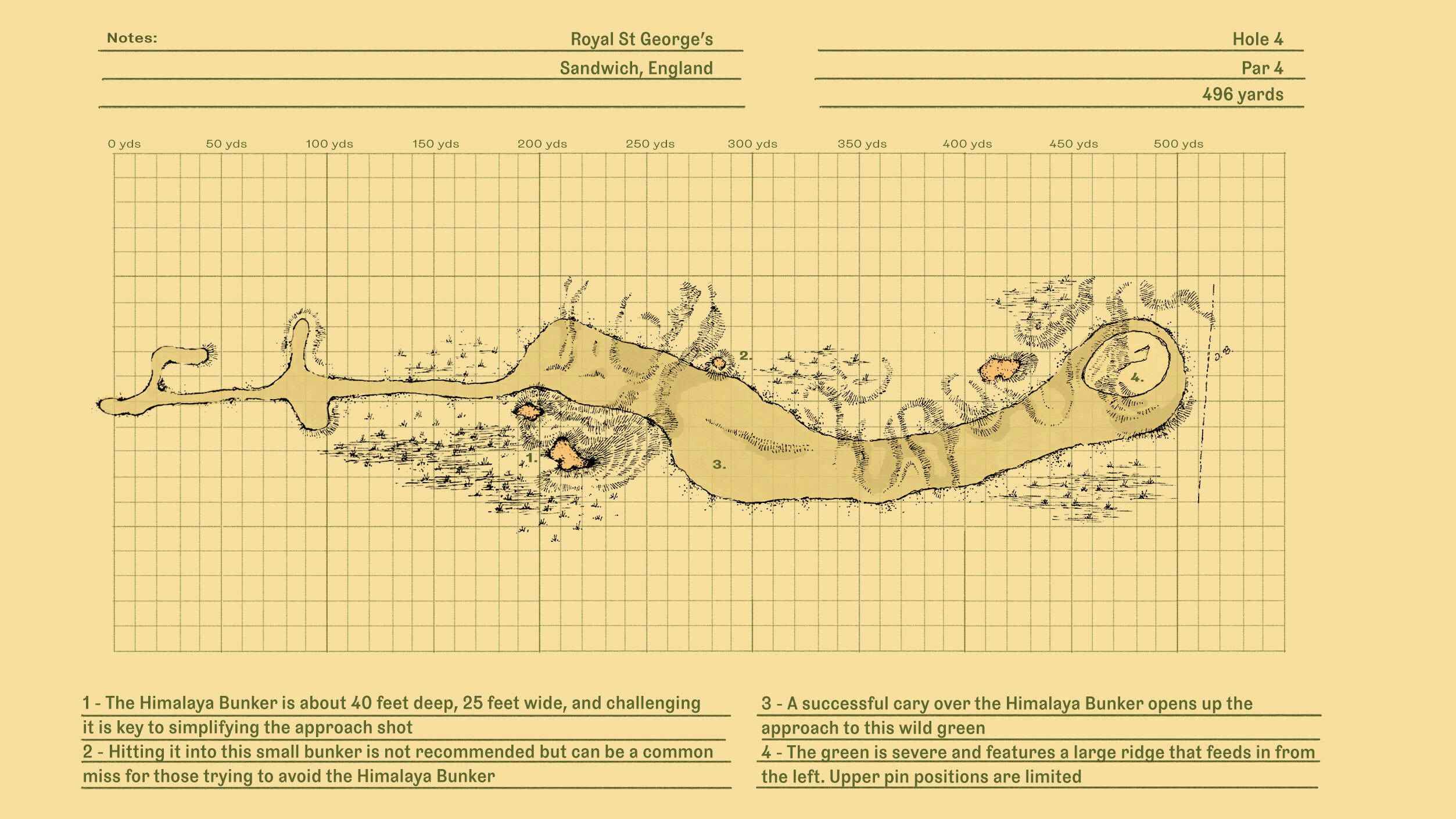

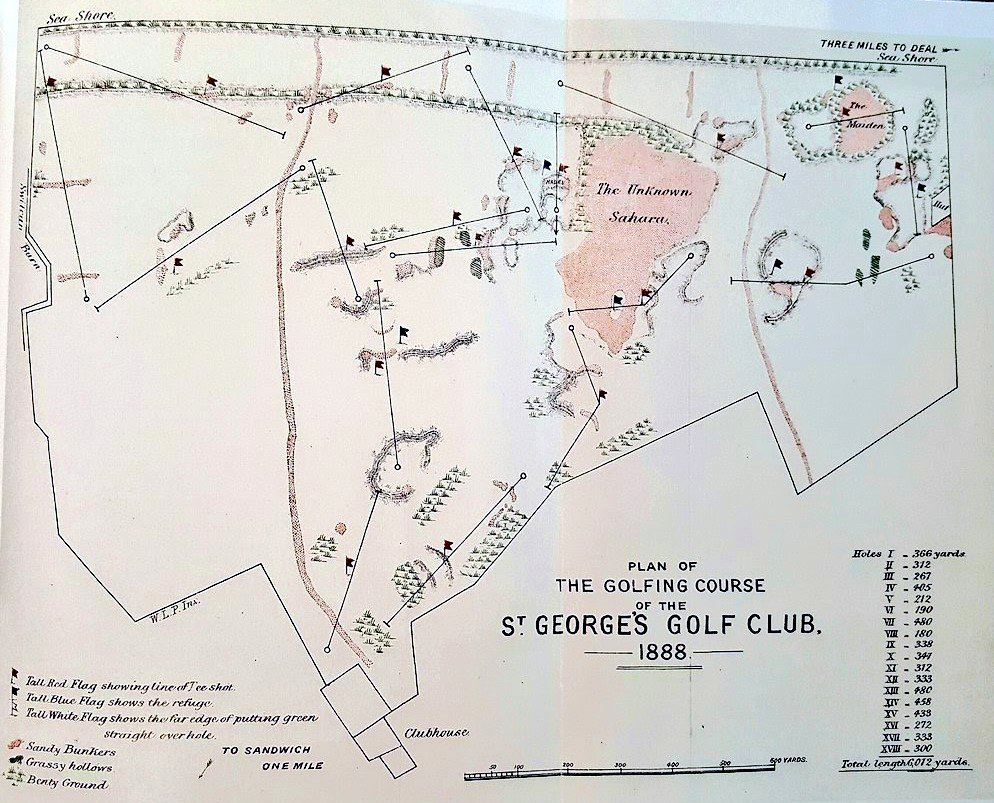

In the late 1880s, London-based, Scottish-born surgeon Laidlaw Purves set out to create an English St. Andrews on the coast of Kent. He discovered a fantastic stretch of seaside duneland near the small town of Sandwich, leased a portion of it from a local earl, planned an 18-hole routing, and, in 1887, founded St. George’s Golf Club, named after England’s patron saint. (The club received the “Royal” designation in 1902.) The course was initially one of the most difficult in Great Britain, featuring many blind shots, forced carries, and fearsome hazards such as “the Unknown Sahara,” “the Maiden,” and “Hades.” After the turn of the century, however, these features — which followed a penal philosophy of design that most Victorian golfers, including Purves, enthusiastically endorsed — began to seem old-fashioned. So, in the years before World War I, the club revised the course, abandoning the blind Maiden hole and replacing many cross bunkers with small, strategically positioned pots. In 1914, Harry Colt, one of the leaders of the new school of golf architecture, visited Royal St. George’s and offered advice related to bunkering. Sixty years later, British architect Frank Pennink belatedly continued this modernizing work, eliminating blind shots and forced carries on Nos. 3, 8, and 11.

In spite of these changes (some of which, it must be said, were likely for the better), Royal St. George’s has retained the wildness, charm, and compelling difficulty that first captured the imaginations of golfers in the late 1800s. While Royal North Devon Golf Club, with its Old Tom Morris design and 1864 vintage, may have a slightly better claim to the title of “English St. Andrews,” few links courses anywhere can rival Royal St. George’s for sheer quality from opening tee shot to final putt.

{{royal-st-georges-about-gallery}}

Take Note…

My colleague Matt Rouches contributed to this section.

Eureka! Club lore has it that Laidlaw Purves surveyed the Sandwich area from the tower of nearby St. Clement’s Church. When he saw the links where he would later build Royal St. George’s, he exclaimed, “By George, what a place for a golf course!”

Chills. After finishing the par-4 second hole, be sure to stop by the small shelter behind the green. Here you will find the name of a young man carved into the walls. A plaque nearby states, “At this spot Piper Murdo McPherson, Cameron Highlanders, from Lochmaddy, North Uist, stood watch during the First World War.” Given its proximity to the Strait of Dover, which provides the shortest crossing of the English Channel, the links at Sandwich have long held strategic significance in England’s conflicts with Europe.

{{royal-st-georges-take-note-gallery}}

007. Ian Fleming, a member at Royal St. George’s and the creator of James Bond, owned a home, still standing today, just off the fifth tee. In Fleming’s 1959 novel Goldfinger, Bond plays a $10,000 match against the villainous Goldfinger at “Royal St. Mark’s,” a lightly fictionalized version of Royal St. George’s. The novel provides a fairly detailed description of the course. In the 1964 film adaptation, this match is relocated to Stoke Poges, an inland Harry Colt course an hour outside of London. One last Bond factoid: the “007” moniker came from a coach service known as the “007,” which traveled between Dover and London.

Best of times, worst of times. In 1894, just seven years after opening, Royal St. George’s hosted its first Open Championship. The winner, J.H. Taylor, shot 84-80-81-81 for a total of 326, still the highest winning score in Open history. Just 10 years later, however, the course found itself vulnerable to the new Haskell ball. On the 36-hole final day, James Braid took advantage of soft conditions to post the first sub-70 round in Open history in the morning, and J.H. Taylor and Jack White repeated the feat in the afternoon. White won with a four-round score of 296.

A different kind of thatch. The vaguely conical, thatched-roof huts scattered throughout the course have real charm.

Favorite Hole

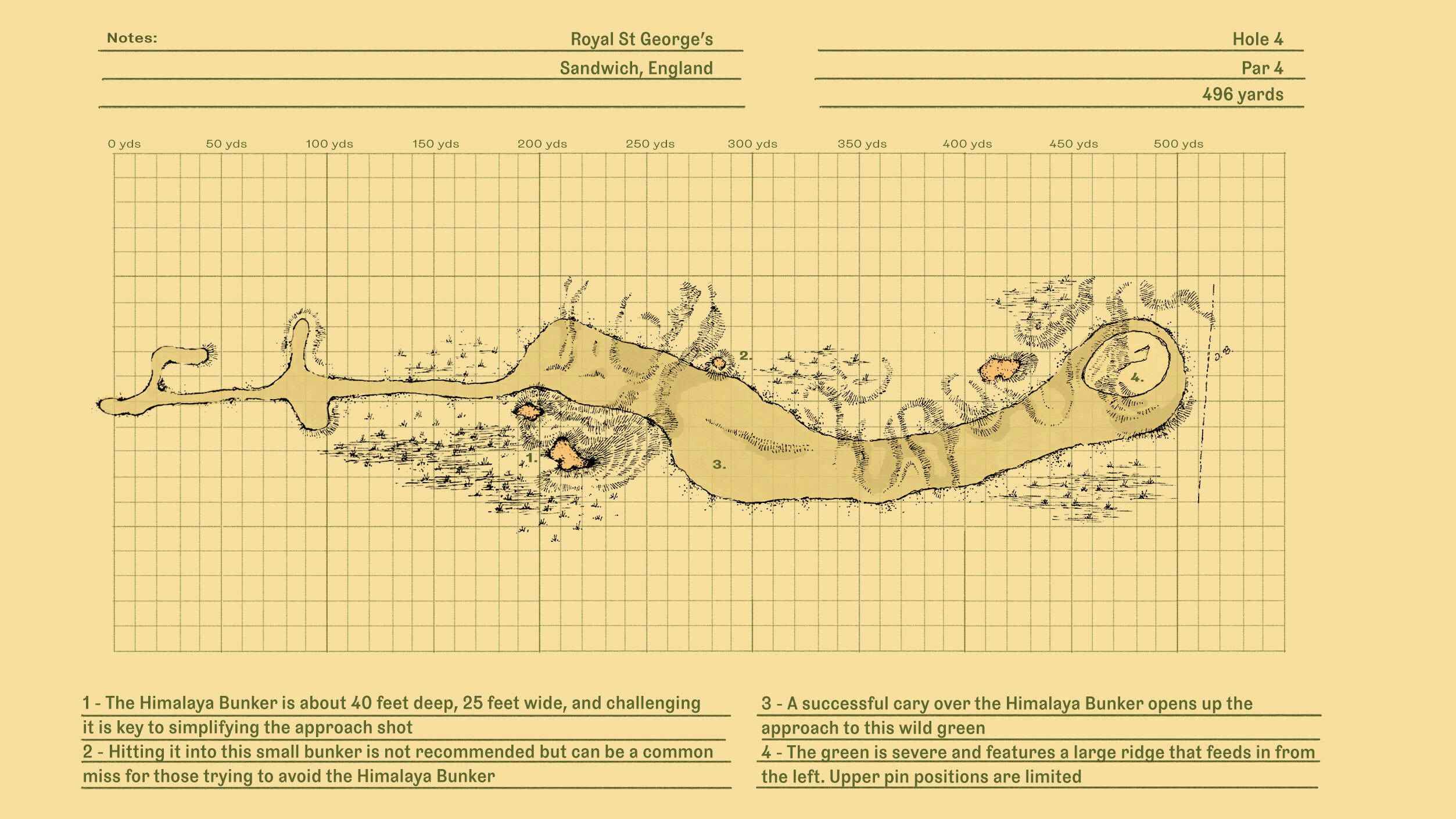

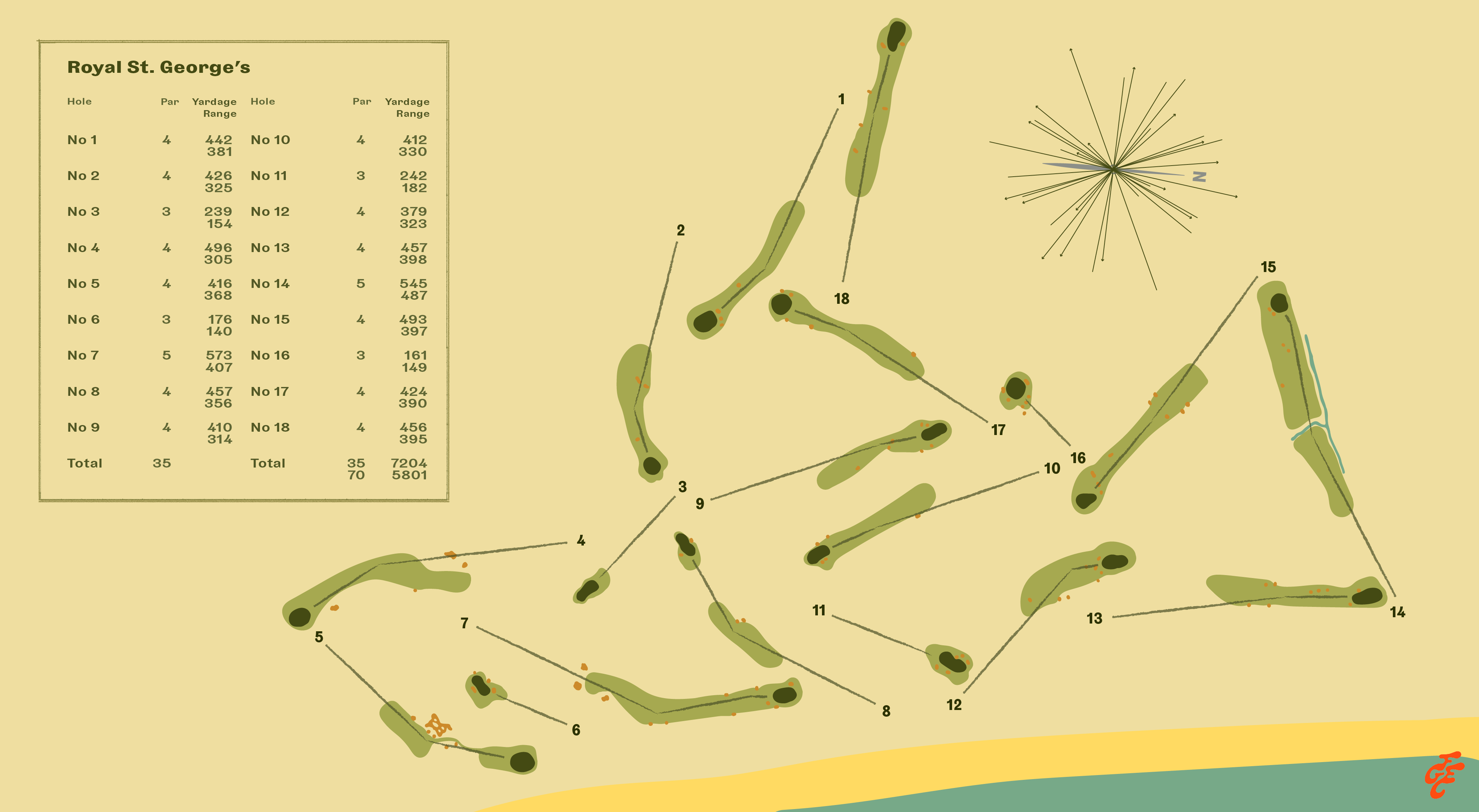

No. 4, par 4, 493 yards

There’s no easy way to play this par 4-and-a-half. There are just slightly less difficult ways.

The view from the tee is frightening. A huge bunker cut into a tall dune blocks the entrance to the right half of the fairway. Left of the bunker and dune, an expanse of fairway is visible. If you play to this safe zone, however, you must stay short of a hidden, startlingly deep pot about 200 yards from the middle tee box, and you will be left with a long, uphill approach over broken ground and a green-side bunker.

In order to keep the hole from getting on top of you, therefore, you must take on the “Himalaya” hazard off the tee. On the other side of the dune, you will find a softly undulating fairway and a clear view of your target: a beautiful, imposing green that climbs up and over a natural shelf. Finding the high back tier, where the pin is almost always located, requires a mighty strike. Alternatively, a lower-swing-speed player might try a running shot that climbs the upslope and uses the feeding contours along the left and back edges.

{{royal-st-georges-favorite-hole-4-gallery}}

Favorite Hole

No. 4, par 4, 493 yards

There’s no easy way to play this par 4-and-a-half. There are just slightly less difficult ways.

The view from the tee is frightening. A huge bunker cut into a tall dune blocks the entrance to the right half of the fairway. Left of the bunker and dune, an expanse of fairway is visible. If you play to this safe zone, however, you must stay short of a hidden, startlingly deep pot about 200 yards from the middle tee box, and you will be left with a long, uphill approach over broken ground and a green-side bunker.

In order to keep the hole from getting on top of you, therefore, you must take on the “Himalaya” hazard off the tee. On the other side of the dune, you will find a softly undulating fairway and a clear view of your target: a beautiful, imposing green that climbs up and over a natural shelf. Finding the high back tier, where the pin is almost always located, requires a mighty strike. Alternatively, a lower-swing-speed player might try a running shot that climbs the upslope and uses the feeding contours along the left and back edges.

{{royal-st-georges-favorite-hole-4-gallery}}

Overall Thoughts

Laidlaw Purves strikes me as an unlikely candidate to have built one of the world’s greatest golf courses.

He adhered to a strict program of design that prioritized fairness above all else. The objective of a golf course, he believed, was to assess the ability to hit the ball “far and sure,” not to engage the player’s mind or, God forbid, to deliver joy. Hooks, slices, and tops were to be punished, and pure strikes rewarded — unfailingly. “Holes should be one or more drives in length,” Purves proclaimed in 1890, “so that any badly driven ball prevents the player reaching the green in the same number of strokes as the player who had driven well. Where the length cannot be obtained, any badly played tee shot should meet a hazard, which will have the same effect.” This does not sound like a recipe for a varied or pleasurable golf course.

So how did Royal St. George’s turn out to be one of the most varied, pleasurable courses in the world?

Well, first of all, it would have been difficult to build a bad course on this site. The landforms at Royal St. George’s are wonderfully varied, from the mountainous dunes that Nos. 2-6 play through, to the sine-wave-shaped undulations of the first, 17th, and 18th fairways, to the infantry rows of mounds crisscrossing the 12th and 13th holes. With each hole, the scale and shape of the ground shifts. The player can’t possibly grow bored or complacent.

But the appeal of the land at Royal St. George’s goes well beyond the measurables of topography. This course is dripping with genius loci. Bernard Darwin said it better than I could in 1910: “Sandwich has a charm that belongs to itself, and I frankly own myself under the spell. The long strip of turf on the way to the seventh hole, that stretches between the sandhills and the sea; a fine spring day, with the larks singing as they seem to sing nowhere else; the sun shining on the waters of Pegwell Bay and lighting up the white cliffs in the distance; this is as nearly my idea of Heaven as is to be attained on any earthly links.” In other words, once Purves clambered to the top of the tower at St. Clement’s Church and saw the Sandwich dunescape, the most important part of his job was done.

Plenty of credit, too, should go to the members and advisers who edited the course between approximately 1908 and 1914. They broke up Purves’ repetitious cross hazards, scattering them into strategically sound arrangements of small bunkers. They also created today’s fifth hole, a thrilling par 4 where a manufactured gap in a dune ridge offers a view of the green to players in the ideal position in the fairway. (As part of the rerouting that made this hole possible, the club scuttled the original “Maiden” sixth hole, a par 3 vaulting over a massive sand dune. This was a small tragedy, perhaps, but a good trade.)

But it’s also clear that Laidlaw Purves himself did some first-rate design work at Royal St. George’s.

His routing is stellar. Defying the 19th-century convention of the out-and-back links layout, Royal St. George’s charts a complex, looping path through the dunes. The course moves counterclockwise but changes direction continually, tacking and weaving, doubling back, alternating between the exterior and interior of the site. Because of the intricacy of the routing, the size of the landforms, and the large amount of space between holes, the player becomes pleasantly lost. Each shot probes a new, previously unsuspected pocket of the property.

Royal St. George’s has possessed this adventurous spirit from the beginning. While Nos. 3, 5, 6, 8, 11, and 16 have shifted from their initial footprints, the basic structure of Purves’s routing has remained intact since 1887.

Equally impressive is Purves’ knack for green siting and design. At many links courses established before the turn of the 20th century, the greens are relatively straightforward. This is not the case at Royal St. George’s. Purves’ original greens are undulating and natural, draped over wild, unpredictable spines and swales. The dune-top second, sharply tiered fourth, perched ninth, and expansive, rambling 13th are especially striking. Because of their lay-of-the-land randomness, these greens are hard to comprehend at first glance, but they reward study.

Laidlaw Purves may have been left behind by the “Golden Age” that started with the new century, but his work at Royal St. George’s has endured as one of the greatest achievements of British golf architecture. It’s time that he got his due.

3 Eggs

Based on the strengths of its topography, routing, greens, and agronomy, Royal St. George’s deserves a three-Egg rating. It does have a few faults: the par 3s, as a set, are a tad underwhelming (which is not surprising, given that all of them are non-original). In addition, several fairways would benefit from widening; members must be deeply familiar with what Alister MacKenzie described as “the annoyance and irritation caused by the necessity of searching for lost balls.” In every other respect, however, Royal St. George’s is impeccable — a leading light of links golf and the Open rota.

{{royal-st-georges-course-tour-01}}

Additional Content

Bob Crosby on the History of Royal St. George’s (Fried Egg Golf podcast)

The Strange Beginnings of Royal St. George’s (Article)

The Simple Design Principles Behind No. 14 at Royal St. George’s (Article)

Tom Doak on Royal St. George’s (Article)

Leave a comment or start a discussion

Get full access to exclusive benefits from Fried Egg Golf

- Member-only content

- Community discussions forums

- Member-only experiences and early access to events

Leave a comment or start a discussion

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Suspendisse varius enim in eros elementum tristique. Duis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere. uis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere.